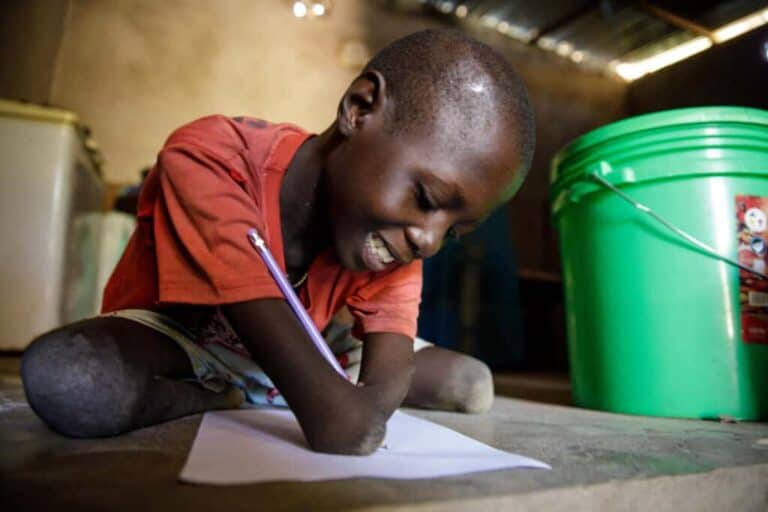

When floods destroyed Mariam’s home and family fields in northern Ethiopia, she thought she had lost everything. “We had no shelter and nothing to eat, so we fled,” the 13-year-old says. “The journey was long and difficult. My mother was pregnant and I was so worried.”

Mariam is from the Afar region, where climate change is forcing many families to leave their homes. And though displacement has taken so much, it has also offered something unexpected: Mariam is now enrolled in school for the first time in her life.

“I love school! One day, I hope to become a doctor. In our village, there is no health centre and I want to able to treat and help my community,” Mariam says. “It’s a bit strange – but without the floods I might never have had this chance to learn.”

At the end of 2021, nearly 37 million children had been displaced within their countries and across borders due to crises like conflict and violence; and another 2.4 million children like Mariam had been internally displaced by disasters.[1] But many children on the move are being deprived of the right to learn, or, when they do enrol, deprived of a quality education.[2][3]

Yet migrant and displaced children are often overlooked in national educational policies and humanitarian response plans – as highlighted by the International Data Alliance for Children on the Move (IDAC) in January, in a blog post that called for action to improve education for internally displaced children through better collection and use of data.[4]

A strategic opportunity

At this week’s Transforming Education Summit, we must work together to galvanize commitments that ensure the right to education of children on the move. Convened in response to a global crisis in education that threatens the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4,[5] the Summit highlights the urgent need to transform the provision, monitoring and financing of quality education in crisis-affected contexts. The Spotlight session, ‘Education in Situations of Crisis’, offers a multi-stakeholder platform for Member States and education partners to collectively commit to concrete actions that will improve access, quality, equity and inclusion of millions of children and youth whose education have been affected by displacement.

As UNICEF Executive Director Catherine Russell recently stated in the run-up to the Summit, “In everything we do, we need to focus greater resources on reaching the most excluded and marginalized children,” she said. “They have been left behind for far too long.” [6]

Serious inequities

Migrant, refugee and internally displaced children are without doubt included among these “excluded and marginalized” children. For instance, a new UNHCR report on education shows that only 68 per cent of refugee children are enrolled in primary school and 37 per cent in secondary school. Among those that are in school, available data show that many face barriers to learning like crowded classrooms and poor teacher to student ratios.[7] These inequities put the future of millions of children at risk.

Missing from the data

Though data are an anchor of achieving the 2030 Agenda, when it comes to reporting on, monitoring and improving school outcomes for children on the move, our efforts are falling short. There are substantial data gaps on access to school, quality of education and educational achievement that prevent this vulnerable population from the chance to thrive in the classroom.[8] In practice, these gaps mean that many children on the move are likely to be missed in education policies and programmes.

More must be done to protect the right of every child to learn – including the often marginalized children on the move. This begins with the collection, analysis and use of quality data to identify those who have migrated or been displaced and are missing from the classroom or falling behind. Indeed, very few countries account for education needs for displaced populations within education sector policies and plans, and even fewer countries explicitly highlight the challenges in accessing education for children on the move when describing progress toward SDG 4.[9]

Disaggregated data – which are key to identifying vulnerable children and their specific needs — on age, gender, migratory status, disability status, as well as family income, educational level and other sociodemographic characteristics, are in most cases lacking.

Working towards a brighter future

Efforts are underway to bridge these information gaps and ensure children on the move stay in school and receive a quality education. These range from:

- Partnerships like the one between UNICEF and Edukans, the NGO that runs the programme that brought Mariam to the classroom;

- UNHCR’s ongoing efforts to generate and use information on forced displacement to strengthen evidence-based programming, including in education;

- UNESCO’s Global Data Portal on Education in Emergencies(EiE) project, which is gathering and standardizing EiE data to ensure children in crises continue to learn;

- the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre’s work to collect detailed data on internally displaced children’s access to education; and

- platforms like the International Data Alliance for Children on the Move, which brings international and regional organizations, academics, NGOs and national governments to the table to improve migration data.

The many ways in which children on the move remain vulnerable must also be highlighted at high-level discussions, like this week’s Transforming Education Summit.

Children on the move deserve the chance for a brighter future. Ensuring their presence in the classroom has major long-term benefits, both in terms of their own lives, their communities and society at large. In order to see quality education for all children, we must work together at local, national and global levels to uphold this right. As UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi recently stated, “Investing in their [refugee children and youth] education is a collective task with far-reaching collective rewards. It will contribute to a more peaceful, more resilient world. It will close that yawning gap between talent and opportunity. The costs of failing to do so will be immense.” [10]

Write us at [email protected] to join this platform, share best practices and experiences, seek partners for collaboration and work together to address the persistent data gaps that harm millions of migrant and displaced children.

About IDAC

The International Data Alliance for Children on the Move (IDAC) is a cross-sectoral global coalition that offers a platform for collaboration and partnerships, with the aim to improve the availability and quality of data and evidence on migrant and displaced children. By highlighting child-specific data gaps and needs in different policy domains, such as access to quality education, IDAC aims to support well-informed policymaking and programming that protect and empower children on the move. IDAC is also working to identify and share good practices and solutions that address data gaps, either collectively or through individual IDAC members.

Footnotes

[1] UNICEF 2022 and UNICEF calculations based on Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre figures. Note that 37 million captures conflict-related displacements, including refugees under UNHCR/UNRWA mandate, asylum-seekers, and conflict-related internally displaced children; it does not include children displaced by disasters like storms and floods.

[3] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR Education Report 2022 – All Inclusive: The campaign for refugee education.

[4] IDAC 2022: Transforming education for internally displaced children – data lead the way.

[5] Sustainable Development Goal 4: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all,” including children, youth and migrants.

[6] Remarks by Catherine Russell, UNICEF Executive Director, Transforming Education Pre-Summit Opening Plenary, 28 June 2022.

[7] UNHCR, UNHCR Education Report 2022.

[8] According to IDAC’s Data InSIGHT publication (November 2021), three in 10 countries and territories do not have age-disaggregated migrant stock data, while four in 10 countries with data on refugees do not provide reliable data on age.

[9] Voluntary National Review (VNR) Synthesis Reports 2018 to 2021

[10] UNHCR, Education Report 2022.