Nearly every minute, a child under 5 dies of malaria

Nearly every minute, a child under five dies of malaria. Many of these deaths are preventable and treatable. In 2022, there were 249 million malaria cases globally that led to 608,000 deaths in total. Of these deaths, 76 per cent were children under 5 years of age. This translates into a daily toll of over one thousand children under age 5.

Malaria is an urgent public health priority. The disease and the costs of its treatment trap families in a cycle of illness, suffering and poverty. Today, nearly half of the world’s population, most of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa, are at risk for developing malaria and facing its economic challenges.

Despite malaria’s heavy toll on health and economy, major inroads were made against the disease from 2000 to 2019 as a result of stepped-up funding and programming. Between 2000 and 2019, malaria mortality rates among all ages halved from 28.8 to 14.1 per 100,000 population at risk. In 2020, the mortality rate increased to 15.2 per 100, 000 population at risk partly due to the disruptions in access to malaria prevention and case management caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and then decreased slightly to 14.5 in 2021 and 14.3 in 2022. During the period 2000 to 2022, percentage of total malaria deaths among children under 5 declined from 87 per cent in 2000 to 76 per cent in 2022.

Success in the fight against malaria is fragile and closely tied to sustained investment. In recent years, there has been a plateau in the funding of the global malaria response. In 2022, the total of international and domestic funding for malaria control and elimination was $4.1 billion, a notable increase from $3.5 billion in 2021. However, the amount invested in 2022 still falls short of the estimated $7.8 billion required to stay on track for the Global Technical Strategy targets.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and response

There is growing evidence that access to skilled and quality malaria services and care may have been negatively impacted by fears of infection and country responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, including lockdown measures, transportation disruptions, and diversion of resources away from essential health services. In 2020, for example, there were significant disruptions to bednet distribution campaigns due to COVID-19 mitigation efforts. There are concerns that these disruptions have also affected other malaria prevention and treatment programmes. Many of these disruptions also coincided with malaria peak season, causing additional concern for the toll that the pandemic has had on malaria mortality and morbidity in children.

Prevention

Sleeping under insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) on a regular basis is one of the most effective ways to prevent malaria transmission and reduce malaria related deaths. Since 2000, the production, procurement and delivery of ITNs, particularly long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs), have accelerated, resulting in increased household ownership and use. Almost 2.5 billion ITNs have been distributed globally since 2004, with 2.2 billion (87 per cent) distributed in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2022, manufacturers delivered about 282 million ITNs to malaria endemic countries, an increase of 22 per cent compared with 2021.

Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have made considerable progress in household ownership of at least one ITNs in recent years, with an average coverage of 67 per cent in 2022, compared to 14 per cent in 2005. However, household ownership of at least one ITN is uneven across countries, ranging from 31 per cent in Angola in 2016 to approximately 97 per cent in Guinea-Bissau in 2019. In addition, only 36 per cent of households in Sub-Saharan Africa had at least one ITN for every two people, which is drastically short of universal access to this preventive measure.

The percentage of children sleeping under ITNs in sub-Saharan Africa increased from 38 per cent in 2012 to 58 per cent in 2022. But despite recent progress in sub-Saharan Africa, the overall use of treated mosquito nets falls short of the global target of universal coverage, and many children are not benefiting from this potentially life-saving intervention. Large country and regional variations exist. For example, during 2022 fewer than 25 per cent of children slept under an ITN in Angola and Zimbabwe, while over 90 per cent of children slept under an ITN in Guinea-Bisseau.

Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa increased ITN use among children under age 5 in an equitable way. This was largely due to free distribution campaigns that emphasized poor and rural areas. The success of this strategy has been reflected in an increased use of ITNs by vulnerable populations.

Care-seeking behaviour

Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for more favourable malaria outcomes. As fever is a key manifestation of malaria in children, particularly in malaria endemic regions, care-seeking for febrile children is crucial to reducing child morbidity and mortality. In sub-Saharan Africa in 2022, 59 per cent of children with a fever were taken for advice or treatment from a health facility or provider. Data show disparities in care-seeking behaviour for febrile children by residence, with those living in urban areas more likely to be taken for care than those in rural areas. Disparities are also observed by wealth, with a 17 percentage point difference in care-seeking behaviour between children in the richest (68 per cent) and the poorest (51 per cent) households.

Case management

Whilst fever is an indicator of malaria in children, it can also be a sign of other acute infections. In 2010, the WHO recommended the universal use of diagnostic testing to confirm malaria infection before administering any treatment. Malaria is diagnosed in febrile children by a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), which involves taking a blood sample from the finger or heel to test for malaria Plasmodium (P.) antigens. In sub-Saharan Africa, testing is low, with only about one in three (30 per cent) of children with a fever receiving medical advice or a rapid diagnostic test in 2022. There was a 11-percentage point gap in testing between the richest and the poorest children (37 per cent vs 26 per cent). Additionally, a greater proportion of children in Eastern and Southern Africa (42 per cent) were tested than in West and Central Africa (23 per cent).

Until recently, the ‘proportion of children under 5 with fever who are treated with appropriate antimalarial drugs’ was the standard indicator for monitoring antimalarial treatment. However, it has become increasingly challenging to track trends following developments in the official recommendations. WHO now recommends universal testing to confirm malaria. In response, many countries have expanded the use of diagnostic testing to focus treatment on those diagnosed with malaria. The current lower levels of antimalarial treatment in febrile children may indicate that anti-malarials are being provided only to confirmed cases. For more information on this issue, see the 2018 edition of the Household Survey Indicators for Malaria Control.

First line treatment

Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is the most effective antimalarial therapy for P. falciparum, the most lethal malaria parasite and the one most pervasive in sub-Saharan Africa. By the end of 2014, most African countries had adopted ACT as the national policy for first-line treatment. The data continue to support, however, that other less effective antimalarial drugs are still commonly used. Treatment of malaria in children with ACT is low in sub-Saharan Africa with just over half (56 per cent) of children treated with anti-malarial drugs receiving the first-line treatment ACT in 2022. In West and Central Africa in particular, ACT treatment is alarmingly low – approximately half that of Eastern and Southern Africa (44 per cent vs 80 per cent). Available survey data indicate that ACT treatment does not differ greatly by residence or wealth within these regions.

Malaria during pregnancy

In sub-Saharan African countries with high malaria transmission, pregnant women are highly vulnerable to malaria infection due to reduced immunity. When infected with malaria during pregnancy, they are more likely to become anaemic and give birth to low-birthweight or stillborn babies. Methods to prevent malaria in pregnancy include the use of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) as well as Intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp).

Regular use of ITNs by pregnant women is a vital intervention in the prevention of malaria among pregnant women. Although some progress has been made, the proportion of pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa who sleep under an ITN remains too low.

Preventing malaria in pregnant women through IPTp with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during antenatal care visits is an effective way of reducing maternal anaemia and low birthweight. Nearly every country in sub-Saharan Africa with a high malaria burden has adopted intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women as part of its national malaria control strategy. In most countries, coverage of antenatal care services is much higher than current levels of IPTp administration, suggesting that there are missed opportunities to expand access to this life-saving intervention for mothers and newborns.

In 2016, the WHO issued a new recommendation that at least three doses of IPTp treatment should be given to pregnant women in malaria-endemic regions, starting in their second trimester, with at least one month between each dose. Many countries are still in the process of scaling up this new recommendation.

In 2022, an average of only 26 per cent of eligible women in sub-Saharan Africa received three or more doses of IPTp. The proportion of women receiving IPTp varies across the region, ranging from 3 per cent at the lowest (Sao Tome and Principe) to 61 per cent at the highest (Ghana).

References

UNICEF, Progress for Children Beyond Averages: Learning from the MDGs, New York, 2015.

Measure Evaluation, Measure DHS, President’s Malaria Initiative, Roll Back Malaria Partnership, UNICEF and WHO, 2013 Household Survey Indicators for Malaria Control.

Roll Back Malaria Partnership, Annual Report 2022. WHO, Geneva, September 2023.

Roll Back Malaria Investing in Malaria in Pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Saving Women’s and Children’s Lives.

UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children 2023, UNICEF, New York, 2023.

WHO, Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria: third edition, WHO, Geneva, 2015.

WHO, World Malaria Report 2023, WHO, Geneva, 2023.

WHO, Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, WHO, Geneva, 2016.

Malaria data

Child Health

Resources

Notes on the data

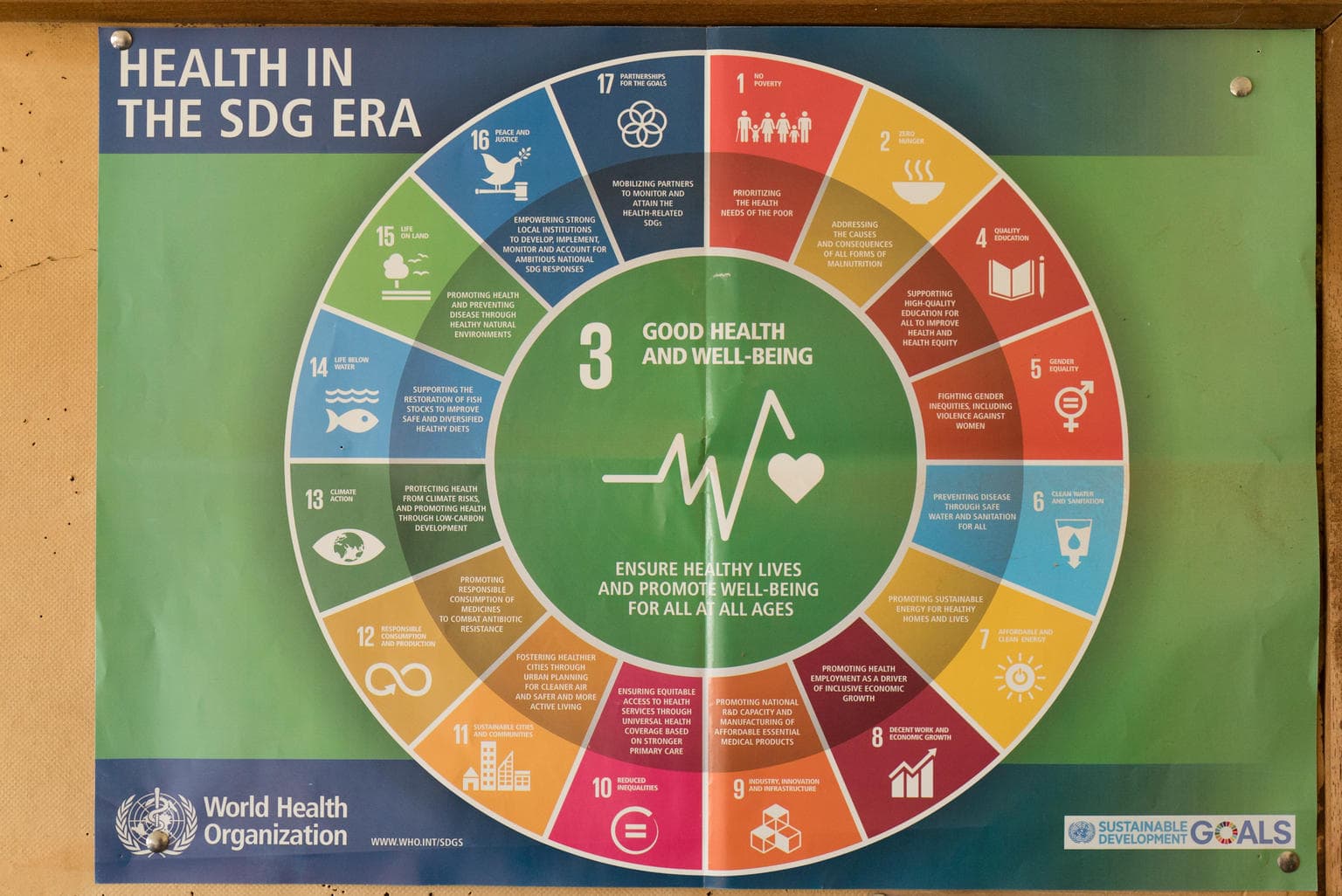

The following is the Sustainable Development Goal indicators for the monitoring of malaria:

| Sustainable Development Goal | Target | Malaria specific indicator |

| Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | Target 3.3 By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases | 3.3.3 Malaria incidence per 1,000 population |

* This indicator refers to antimalarial treatment among all children with fevers, rather than among confirmed malaria cases, and thus should be interpreted with caution.

For additional information, visit the latest Household Survey Indicators for Malaria Control manual.