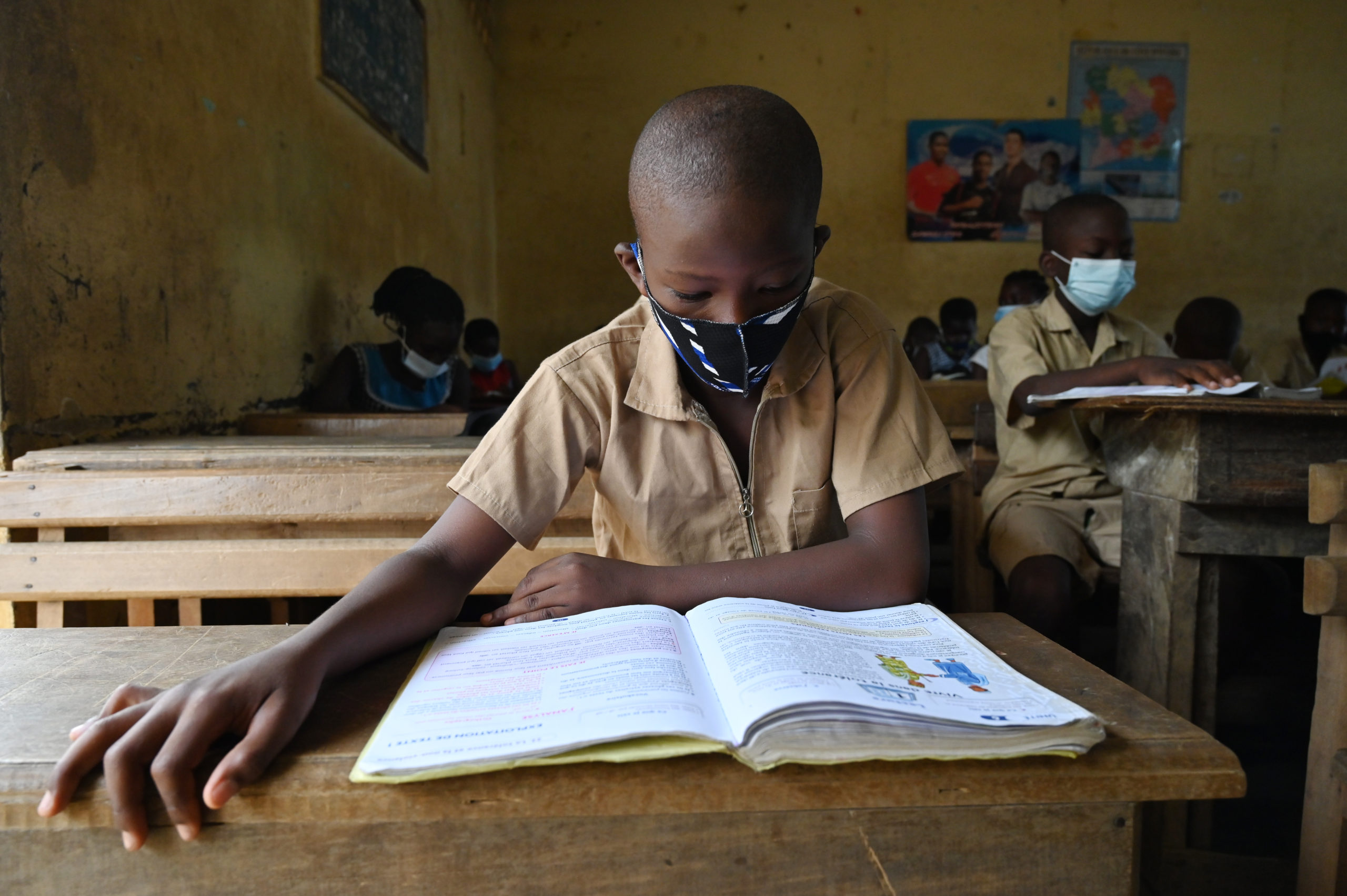

For a child, poverty can last a lifetime

In the eyes of a child, poverty is about more than just money. Very often children experience poverty as the lack of shelter, education, nutrition, water or health services. The lack of these basic needs often results in deficits that cannot easily be overcome later in life. Even when not clearly deprived, having poorer opportunities than their peers in any of the above can limit future opportunities.

In most countries, children make up between a third to almost half of the population. Unless child poverty is specifically monitored, policy makers may have the misconception that progress is being made to reduce poverty, when in reality a large proportion of the population could be stagnating or worse off. This could be the case if improvements in access to health care and literacy rates are observed at the aggregate, national level while children are not taken to clinics and children are not going to school.

A major step-forward recognizing the importance of child poverty, promoted by the tireless work of NGOs in collaboration with NSOs/Ministry of Planning and other government counterparts, is that the SDGs explicitly require measurement of multidimensional child poverty.

SDG 1.2.2 Proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

Measuring child poverty means measuring the experience of the whole child

This means, on the one hand, that child poverty ought to be measured at the child level, and all the dimensions must be assessed simultaneously for the same child. Although this introduces some data challenges, traditional household surveys such as MICS and DHS provide the required information in all dimensions of child poverty.

All children under the age of 18 should be counted. Total estimates for all children should and can be calculated. In addition, when possible, sub-groups such as 0-5, 6-11, and 12-17. Fortunately, available data sets allow these estimates to be carried out. This implies that it is very easy to go beyond just disaggregating household-level poverty information by age to properly estimating child poverty at the individual level.

Child poverty measurement should be based on deprivation of child rights for each individual child. Although Income and consumption insufficiency is another important dimension (linked to the right to a minimum standard of living), it should be analyzed separately given it is nature and characteristics. For example, children are not supposed to earn a living. Moreover, monetary income (or consumption) poverty is usually measured at the household level, not for individual children. In addition, child poverty could be a cause or a consequence of monetary poverty and monetary poverty could be a cause or consequence of child poverty. Monetary poverty (of the household) and child poverty (deprivations of rights) therefore measure different, but complementary issues, and one does not substitute for the other. Both in the short and in the long term (across generations), there are feedback mechanisms between the two. Thus, cross-tabulating the information about individual child poverty with the monetary poverty of the households in which children live is useful.

Internationally comparable measures of child poverty

In order to be able to make internationally comparable assessments of the extent of child poverty, a measurement that uses the same parameters across countries is needed. All the dimensions included here are rights constitutive of poverty (i.e. those rights in the Convention on the Rights of the Child which directly and fundamentally require material resources to be fulfilled). Indicators have to be valid and reliable, and must be available across a large number of countries. The thresholds used to determine deprivation for the indicators in each dimension are internationally agreed minima (e.g. in the context of the SDGs or the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene).

In addition, in all dimensions, both severe and moderate (that includes also the severe) thresholds are used. (See Table of Dimensions, Indicators, and Thresholds) For the estimates below, exactly the same dimensions and the same indicators have been used for all countries.

Figure 1 below presents the profile of child poverty using severe thresholds. It shows the percentage of children without any severe deprivation (a little over half of the children worldwide). About a third of children suffer one severe deprivation while close to 15 per cent suffer exactly two deprivations. Less than 3 per cent of children suffer exactly three deprivations. Less than 1 per cent of children suffer either four or five deprivations. On average, children suffer two-thirds of a deprivation (at the severe threshold).

In the Figure 2, the profile of child poverty using moderate thresholds is presented. It shows the percentage of children without any severe deprivation (about 1 in 5 children worldwide). About a third of children suffer one moderate deprivation while close to a quarter of children suffer exactly two deprivations. Around 10 per cent of children suffer exactly three deprivations. Less than 4 per cent of children suffer four five deprivations. Less than 1 per cent of children suffer five deprivations. On average, children suffer 1.4 deprivations (at the moderate threshold).

Resources

Notes on the Data

International standards, local relevance, and cross-country comparability

While the SDGs explicitly say that countries can define their own way to measure poverty, certain minima across countries ought to be respected. Child rights are universal, meaning all children should enjoy the same rights independently of the country in which they were born. The way to assess if a right is deprived cannot be adjusted downwards for certain children (whether they are from rural areas, belong to a linguistic minority, or live in a poorer country).

Thus, in spite that in some countries some items may not be needed (e.g. heaters in the tropics), all children should enjoy a minimum of quality housing. Regardless of where they live, if their dwellings do not meet hygienic and privacy requirements, the children should be considered deprived.

This does not solve all international comparability problems. Nevertheless, concentrating the measurement of child poverty on the rights that constitute poverty and accepting the principle of universality of rights, can go a long way to ensure that estimates of child poverty are useful for policy-making while at the same time providing a modicum of comparability across countries.

References

Child poverty reports, The Global Coalition to End Child Poverty.

ESCWA, OPHI, League of Arab States and UNICEF, Arab Multidimensional Poverty Report, ESCWA, Beirut 2017.

United Nations Children’s Fund, Pobreza infantil en America Latina y el Caribe, UNICEF/ UN ECLAC, Santiago 2010.

Minujin, Alberto, Child poverty in East Asia and the Pacific: Deprivations and disparities: A study of seven countries, UNICEF, Bangkok 2011.